Identity

Usefulness and services of the tree :

Features and characters of the individual

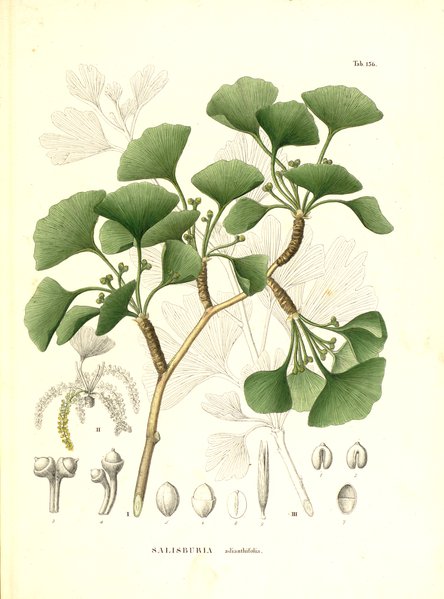

This tree has two-lobed leaves in the shape of small fans, as well golden yellow fruits. Nicknamed the tree of “40 coins” because of its golden autumn leaves, it illuminates the small Parc des Muses. This seasoned tree comes from a species of coniferous – modern-day dinosaurs – which are a symbol of longevity in Asia. It is already showing signs of old age, but it is being given great care and attention to ensure it still has a good few years ahead. The risk of its branches falling has lead to it being surrounded by a fence, protecting not just its roots but also the heads of everyone walking underneath!

The sun tree

Ginkgoes have the reputation for being incredibly resistant, to pollution, radiation, viruses: they are true forces of nature. They have witnessed the evolution of our planet. The Chinese and Japanese consider them sacred trees, symbols of immortality.

The sacred tree

In the Parc des Muses in Molenbeek, you may approach the formidable Ginkgo biloba with a certain awe. This individual is the largest and oldest known specimen in the capital. Around 150 years ago, it grew in the open countryside. ‘Total respect,’ say some neighbourhood locals when they learn its age.

Walkers are invited to admire its exceptional silhouette from a good distance. It is harmonious and well-balanced. Its main limbs, short trunk, and root buttresses are powerful. If you pass by, gaze deeply into its foliage: bright green in the spring and saffron gold in autumn (November), it delights the eye and brightens the park.

And you can go ahead and approach for a closer look, but not too close. Because, despite all appearances, the largest ginkgo in Brussels is in fragile health. In reality, it is hollow: you can tell because of its fluted trunk, and the fissures and bulges in its bark. The tree is at war with a fungus that is eating it from the inside. The Department of Notable Trees of the Region is its ally in this battle. A triple protective perimeter has been installed around it.

This way, its roots do not get trampled on. At its foot, grasses can grow and leaves can freely fall and decompose. It's a question of generating a soil similar to that of the forest: loose and airy, rich in humus. This tactic has allowed the ginkgo to regain its strength. The latest reports indicate that it has successfully isolated and neutralised the fungus in compartments.

As long as it is not further weakened, this individual is likely to live to a ripe old age. It probably won't reach a millennium, like certain ginkgoes have been known to do in Asia. But with a little luck, it could easily last for another century and a half. What will Molenbeek be like then?

Long may he live. And anyone who dares to penetrate his sacred zone, beware: this specimen has been known to drop a branch now and then …

Symbol of immortality

Ginkgoes appeared on Earth +-270 million years ago. At that time, the continents had yet to separate and the landscapes were populated by ferns and giant horsetails, as well as conifers. This tree had its heyday in the Jurassic period. It would have existed side-by-side with the dinosaurs, and witnessed their extinction. Among the dozen species of ginkgoes, only one has survived the vicissitudes of evolution: the biloba.

In the late 17th century, all that Europeans knew of the ginkgoes came from fossilised prints of its leaves. They believed the tree to be completely extinct, like the giant ferns and dinosaurs. So when the German botanist Engelbert Kaempfer discovered a living specimen in Japan, he couldn't believe his eyes. In fact, this ‘prehistoric’ tree was already being cultivated by Chinese monks in the 12th century.

Since then, the ginkgo has practically vanished from the forests of Asia. But it's sanctity, beauty and strength have made it a protector. So it has survived in this role, in front of Buddhist and Shinto temples, in palace courtyards and the entrances to public spaces in Japan. Its many medicinal properties have also helped to save it. It is cultivated throughout the entire world. Its hardiness has made it a tree of the city: it adapts very well to our parks and avenues.

The ‘polynomial’ tree

The most striking thing you will notice about this tree in passing is the highly unusual shape of its leaves. They look likes little fans measuring (an average of) 6 centimetres across. This fan-shape can be seen in the hair of the greatest sumo wrestlers and is the emblem of the city of Tokyo. The Chinese describe the shape more as a ‘duck’s foot’. Close examination reveals a subtle indentation that splits the blade of the leaf into two lobes. Hence the name of the species: biloba.

The little ‘fruits’ of the tree are no less unusual. To start with, they are not actually fruits: they are naked ovules, or ‘pseudo-fruits’. They are the origin of the name of the ginkgoes: ‘silver apricots’ in Japanese. In springtime, they are a pale green colour with a silvery sheen. They later take on the appearance of golden yellow plums.

The ginkgo is often referred to as ‘the 40 ecu tree‘. However, this is not a reference, as one might think, to these golden fruits. It takes its name from a transaction dating from 1780. Mr. de Pétigny, a wealthy inhabitant of Montpellier, is said to have purchased several ginkgoes from a London horticulturalist. For each specimen, he is said to have paid the sum of 40 ecus.

Whether or not this gentleman of Montpellier ever felt buyer’s remorse has been lost to history. But the fact is that, when the golden fruits fall to the ground and begin to decompose, they release a terrible smell, reminiscent of rancid butter or vomit. The story also does not say whether the buyer had tasted the nuts that are concealed at the heart of the fruit. When properly handled, they are delicious. They play an important role in the tea ceremony and are highly prized as ingredients in refined dishes throughout the Far East.

This tree can turn entirely to gold. In October-November, as everything else turns grey, the leaves and fruits become a blazing gold. The botanist Kaempfer referred to it as ‘maidenhair’. When the leaves are blown by the autumn winds, they are scattered on the ground like pennies from heaven. In this way, the gingko could just as well be the tree of a thousand ecus. In the parc des Muses, there is a ‘sun’ that shines when the days grow dark.

Defining evolution

This tree has not only left traces in the language. In evolution and in the classification of plants, the ginkgo occupies a special place, too. It is a species, a genus, a family and an order. That's all!

The gingko is often assumed to be a hardwood, but it actually belongs to the large family of conifers. Yet, it does not produce cones. Its buds look like tiny green cones, but in fact they are clusters of curious looking, very short twigs, from which the leaves emerge in clusters.

Like all conifers, the ginkgo is one of the gymnosperms: plants whose seeds or ovules are completely bare. Unlike other conifers, its ovules are not protected by the scales of a cone, like the pine nuts inside pinecones, for example.

It is also distinguished by a particular mode of reproduction. Botanists refer to this tree as ‘dioecious’: meaning that it has two houses. This is because in ginkgoes, there are two different sexes. Mr. Ginkgo bears male flowers: ‘catkins’. They are clustered in bunches and hang from a stem like grapes. Their pollen is disseminated by the wind. He fertilizes Mrs. Gingko who has ovules: two small bumps at the end of a stem. They secrete a tiny, sticky droplet that captures the particles of pollen in the air. They then turn into ‘silver apricots’ and later ‘golden plums’. Despite their name, they are not fruits, but in fact ovules. As they are completely naked, they are fairly fragile. They need to take root quickly or else they will die.

How has the ginkgo been able to pass down through evolution with such a primitive mode of reproduction? What is the key to its immortality? It is still a well-kept secret.

(Story and photos created by Priscille Cazin https://www.sylvolutions.eu)

This portrait is enriched with an illustration from the Belgian Federal State Collection on permanent loan to the Meise Botanical Garden. See attached. Thanks to the library (heritage collection) for this contribution. https://www.plantentuinmeise.be/en/home/